Biography of Munch

(December 12, 1863)

The Kristiania - Bohème and Early Exhibitions

Girl Kindling a Stove. 1883, Oil on Canvas, 96.5x66cm, Private Collection

In 1882, Munch shared a rented studio with six other artists, supervised by the painter Christian Krohg, who was considered the “dean of the Bohemian painters.” Under Krohg’s influence, Munch took part in the organization of the first Høstutstilling, free of the Norwegian Kunstforening’s sponsorship and censorship. This was Munch’s first public exhibition, and as subject matter the participating artists exhibited selected studies of the urban poor and Norwegian landscapes.

In autumn 1883, Munch attended Frits Thaulow’s Friluftsakademi at Modum. He showed his first large oil, Girl Kindling a Stove at the Open Air Academy’s Autumn exhibition and was awarded a small grant to study in Antwerp and Paris. Munch soon added to his academic training experiments in a semi-Impressionist Naturalism, as advocated by Krohg and Thaulow in their efforts to create a national landscape style based on plein-air painting and influenced by the contemporary art of Paris. This new style also underlined the process of Norwegian independence from Sweden, linked with parliamentary liberalism and ideas of radical social reform.

While in Antwerp, he exhibited Inger in Black at the World’s Exhibition, his first international showing, which was panned by critics. His Paris stay included visits to the Salon and the Louvre, absorbing the techniques of master painters while he continued developing his style of landscapes.

Upon returning to Norway, Munch became entrenched with the growing number of writers, students and artists who made upt he Kristiania-Bohème. It was in 1885-1886 that the Kristiania-Bohème was most public, and this is the time that Munch spent working on The Sick Child, a melancholy memorial to his deceased sister which he had begun in Paris and finished in Noway.

Sister Inger. 1884, Oil on Canvas, 97x67cm, Nasjonalgellereit, Oslo

The Sick Child. 1885-1887, Oil on Canvas, Tate Gallery, London

Norwegian Landscape, Drawing, 22x16.5cm, Falmouth Art Gallery

The group’s spokesman and anarchist writer, Hans Jaeger, preached an anti-bourgeois lifestyle of freedom and sexual liberation, social equality, and the rejection of Christianity. This encouraged a fundamentally subjective and introspective quality to the art of the time.

In accodance with Jaeger’s dictum of working from personal experience, The Sick Child represents a variation of Impressionist technique. In the lengthy alterations, Munch built up coagulations of paint into which the actual image was more scratched than painted and over which a veil of paint was placed and removed during a partial repainting. This experimation created effects similar to those of James Ensor and Vincent van Gogh in the late 1880s, and are recognized as precursors of 20th Century Expressionism.

Nevertheless, 1886 Norway was unappreciative of the work, and his showing at the 1886 Høstutstilling exhibition was attacked by both critics and fellow artists. Only Jaeger and the newspaper Dagen came to Munch’s defense, calling it the intuitive work of a genius.

While in Norway, Munch began an affair with Emily “Millie” Ihlen Thaulow, the wife of Fritz Thaulow’s brother, Carl. He also began to express himself in writing, setting forth an autobiographical journal which served as a reference for the majority of his paintings in the early 1890s. During this period, Jaeger was involved in a love affair with Krohg’s wife; and undoubtedly this and Munch’s own numerous affairs intensified his emotional expressions of women, love and death.

Munch held a one-man exhibition of his works at the Studentersamfund, Kristiania in April and May of 1889. This was his first substantial showing, held at the Student Organization in Kristiania. This was an event unprecedented in Norway aside from a celebration of the respected academic landscape painter Hans Fredrik Gude. In place of The Sick Child, Munch substituted Spring, a massive new painting on the same theme, painted in a more conservative and Naturalist style.

Despite the controversy surrounding him, the collection received a favorable review from Christian Krohg. This led to an award of a three-year grant, contingent upon study with a drawing tutor. In 1889 Munch spent his first summer at the Norway resort Åsgårdstrand on Kristianiafjord (now Oslofjord), the retreat to which he consistently returned and which for 20 years provided the setting for innumerable paintings.

That autumn, Munch returned to Paris, where he studied under Léon Bonnet. Although Munch had briefly visited exhibition in Antwerp and Paris in 1885, it was the Exposition Universelle of 1889 and other Paris art exhibitions where Munch absorbed extensive examples of contemporary paintings.

Less than a year after his return to Paris, Munch relocated to St. Cloud, where he continued writing and painting. Shortly thereafter, word of the unexpected death of his father caused yet another spiritual and emotional crisis in Munch, causing him to reject Jaeger’s anti-Christian teachings. His expression of emotion through art reached a new pinnacle in the spring of 1890, with two of Munch’s most important works, Night in St. Cloud, a memorial to his father, and Spring Day on Karl Johan Street, a sunny view of people promenading on Kristiania’s main thoroughfare in spring. Adapting principles of Neo-Impressionism, the two images contrast representations of death and grief, then life and joy.

Night in St. Cloud. 1890, Oil on Canvas, 64.5x54cm, Nasjonalgallereit, Oslo

Spring Day in Karl Johan Street 1890, Oil on Canvas, 80x100cm, Bergen Billedgalleri

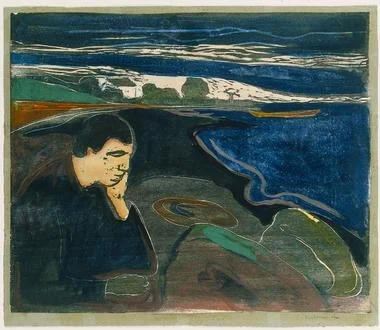

Also in 1890, Munch’s paintings were shown at the Autumn Exhibition. (Evening, now commonly known as Melancholy, is considered the first depiction of his St. Cloud Manifesto concept, serving as an early motif for his Frieze of Life works.) Aside from encouragement from Krohg, his contribution to the exhibition went relatively unnoticed; and Munch returned to France after receiving another state scholarship.

In 1891, he drew illustrations for Alruner, a collection of Emanuel Goldstein’s poetry. Other drawings created during this phase include work for publication with (but not illustrations for) writings of Norwegian poets Vilhelm Krag and Sigbjorn Obstfelder. It was during this time that Munch did intial paintings of The Kiss and Despair and outlined a range of emotional and subject matter to which he returned repeatedly and which formed the foundation for a group of paintings entitled Love.

The Kiss. 1897, Oil on Canvas, 99x81cm, Munch Museum

Melancholy (Evening). 1894-96, Woodcut with Hand Coloring, 37.7x45cm, Cleveland Museum of Art